How the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) plays the game: communicate football's social responsibility

Cómo la Unión de Asociaciones Europeas de Fútbol (UEFA) juega el juego: comunicar la responsabilidad social en el fútbol

Autores

da Rocha, Fernando Jesús

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5794-0114

University of Beira Interior, Portugal

Morais, Ricardo

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8827-0299

University of Porto, Portugal

Datos del artículo

Año | Year: 2022

Volumen | Volume: 10

Número | Issue: 2

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17502/mrcs.v10i2.593

Recibido | Received: 1-9-2022

Aceptado | Accepted: 10-10-2022

Primera página | First page: 379

Última página | Last page: 392

Resumen

In this article, we seek to analyze how the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) communicates on the social network Facebook, considering social responsibility issues. Based on the idea that sport in general, and football, in particular, can play an essential role in social transformation, we try to understand whether football's governing body in Europe has used digital social networks to communicate actions aligned with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To achieve this objective, we use a mixed methodology, which determines the nature of the research as quali-quantitative with the use of the content analysis technique in a particular case study since it specifically analyzes the UEFA Facebook page and 257 publications made during the year 2021. Thus, we seek to understand if the institution plays the game concerning social responsibility and what contents and objectives stand out in this communication.

Palabras clave: comunicación integrada, organizaciones, redes sociales, deportes, objetivos de desarrollo sostenible,

Abstract

En este artículo buscamos analizar cómo la Unión de Asociaciones Europeas de Fútbol (UEFA) se comunica en la red social Facebook, considerando temas de responsabilidad social. Partiendo de la idea de que el deporte en general, y el fútbol en particular, pueden jugar un papel fundamental en la transformación social, tratamos de entender si el órgano rector del fútbol en Europa ha utilizado las redes sociales digitales para comunicar acciones alineadas con los 17 Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible ( ODS). Para lograr este objetivo, utilizamos una metodología mixta, que determina el carácter cuali-cuantitativo de la investigación a partir del uso de la técnica de análisis de contenido, en un caso de estudio particular, ya que analiza específicamente la página de Facebook de la UEFA y 257 publicaciones realizadas durante 2021, buscando comprender si la institución juega el juego de la responsabilidad social y qué contenidos y objetivos se destacan en esta comunicación.

Key words: integrated communication, organizations, social media, sports, sustainable development goals,

Cómo citar este artículo

Rocha, F.J.D. & Morais, R. (2022). How the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) plays the game: communicate football's social responsibility. methaodos.revista de ciencias sociales, 10(2): 393-409. http://dx.doi.org/10.17502/mrcs.v10i2.593

Contenido del artículo

1. Introduction

Racism, xenophobia, homophobia, sexism, and other forms of intolerance have been greatly demonstrated in our societies. Such growth in demonstrations has been accompanied by an increase in campaigns and communication strategies to raise awareness of the importance of respecting human rights.

Football, as one of the sports most played in the world and followed by billions of people, can, in this context, be a privileged stage to a socially responsible communication, especially considering its ability to reach and infiltrate the most varied segments of society (Walters & Tacon, 2011)Ref48. Sociologist Richard Giulianotti, one of the world’s leading researchers on the historical and sociocultural dimensions of soccer, states that “although it is the world's premier team sport, it was only in the 1960s that soccer's social importance received substantive and separate attention from social scientists and historians” (Giulianotti, 1999, p. 18)Ref16. The author adds that social sciences especially highlight soccer, among collective competitions, as a distinct space for expressing communal identities (Giulianotti, 1999)Ref16. Thus, in this work we start by drawing attention to the role that football can play in terms of social responsibility; a role that has often been underestimated. We believe that sports organizations, through strategic communication, using the adequate tools to communicate, namely in the digital environment, can be a vector of social transformation.

In this work and in order to deepen this debate, we aim to verify the importance that the Union of European Football Federations (UEFA) attaches to the communication of social responsibility. For this purpose, we consider the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, conceived by the United Nations in 2015, as a beacon of social responsibility content. It should be noted that this study does not intend to properly investigate UEFA's alignment with the 2030 Agenda in meeting specific sustainability indicators set out in the agenda, despite this observation is extremely important. The intention is precisely an analysis of the emphasis that UEFA can give to communicating social responsibility. For that, we take the text and the deepening of each SDG to indicate when a message addresses content that presents itself with a social and/or sustainable theme, highlighting football as an important factor in social life. Not just as a mere transmitter of sports events and activities but as a potential driver of social transformation, it also could seek to express values, through its communication channels.

Combining quantitative and qualitative techniques, such as a case study and content analysis, we analyze the content of Facebook posts to understand the dimension and visibility they give to social issues. It is important to note that the observation focuses on the year of 2021, but necessarily considers that strategies aimed at communicating social responsibility, when they exist, result from an implementation that takes place over time, sometimes over several years, configuring, thus, a practice, and not just isolated actions in this analyzed period.

Yet, the first results denote actions limited in time, usually associated with the celebration of world days, which reveal attention on the part of the governing body of football in Europe, but at the same time denotes an attention that is sometimes too limited in time. Also noteworthy are the various initiatives to which the organization is associated, which also seems to be part of its social responsibility strategy. If, as UEFA’s director of football social responsibility says, in a wide-ranging interview for UEFA website1, “they invested 12 million euros in social responsibility activities” in 2021, in this work we try to understand how they communicate their actions in social media, considering that today digital presence is crucial to reach the different sectors of society, but above all the younger ones, important actors in the development of a more just and respectful society.

2. Communication at the heart of organizational decisions

Organizational communication is a concept that unites two independent but correlated fields: organization and communication. Communication plays a substantial role in contemporary social life, as it “travels between homes around the world through digital networks and at very high speed” (Cegalini & Rocco Junior, 2019, p. 100)Ref8, emphasizing its importance in the organizational paradigm. It is doubtful that an organization will succeed without communicating. Historically, this relationship of interdependence has been the subject of a great effort by the main theorists on the subject (Silva, Ruão, & Gonçalves, 2020)Ref42.

It is essential to highlight that we are not restricted to sending messages to an external audience when we talk about communication. The communicative process can interconnect different individuals and their cognitive universes that make up an organization towards a common goal (Kunsch, 2018)Ref28. Furthermore, these individual and social actors act together in the light of the symbolic activity, such as communication, capable of involving and interpreting meanings, that establish an organization (Silva et al., 2020)Ref42. Therefore, talking about organizations also presupposes the sharing of information, cultures and meanings, that is, talking about communication, which predates the very constitution of organizations (Ruão, Salgado, Freitas, & Ribeiro, 2014)Ref39, configuring two activities that touch each other in complementarity.

Communication, mainly digital, based on new technologies, has established a fruitful relationship between organizations and audiences (Gonçalves & Elias, 2013)Ref18, starting to positively impact people and society in general (Vieira, 2004)Ref47. Given this context, communication must be considered a phenomenon, a fundamental social process, and not merely an issuer or transmitter of information from a vertical relationship (Kunsch, 2018, p. 14)Ref28.

Faced with so many theoretical aspects and approaches that enrich it over time, Organizational Communication can now be considered an established area in Communication Studies (Silva et al., 2020, p. 114)Ref42. As one of the significant contributions to the discipline, we can mention the integrated organizational communication model, developed by the researcher Margarida Kunsch (2003)Ref26, which can be applied in companies, entities and institutions. It perceives integrated communication under a convergent prism encompassing institutional, marketing, internal and administrative communication, allowing a harmonious and strategic vision of communication resources. Acting synergistically, they are aligned with the organization’s global paradigms, placing communication at the center of organizational decisions.

In a more recent study, the author Margarida Kunsch (2018)Ref28 starts to address an increasingly recurring subject. When discussing institutional and marketing communication, which are part of the constitution of integrated communication, she argues that organizations should look beyond the relationship with the business's target audience. As they are part of a social ecosystem, organizations need to be aware of their role, assuming responsibilities that “go beyond the manufacture of products and the provision of services, to obtain profits” (Kunsch, 2018, p. 16)Ref28

According to Silva et al. (2020)Ref42, issues oriented to ethics and social responsibility have been a trend in Organizational Communication studies. Today, the public already expects transparency, ethical behavior, and social sustainability actions from organizations. The great challenge, in this sense, according to Kunsch (2016)Ref27, is for organizations to demonstrate that this behavior overlaps with economic interests that confer a supposed interest in social well-being, solely and exclusively, intending to gain image. As a consequence of this imposition of socially responsible behavior by the public (Silva et al., 2020)Ref42, there is no other way for the organization to communicate than being honest and credible (Vieira, 2004)Ref47, consistent with its actions, communications and placements.

Suppose the communication system established by the organization is intended only to act rhetorically on public opinion, to persuade it and win its support. In that case, authentic communication will not be established in constructing dialogic attitudes supported by truthful reporting language (Vieira, 2004, p. 32)Ref47.

In a digital age, with the dispersion of digital media, organizations can no longer control when or to what extent audiences are affected. Therefore, the institutional discourse must be coherent (Kunsch, 2018)Ref28. Strategic management of communication in the organizational environment becomes urgent for identifying audiences and organizations (Rocco Junior, Carlassara, & Parolini, 2016)Ref36, with the integration of the organization's global guidelines, transparency and positioning that makes sense and conveys truth.

3. Integrated communication in sport: strengthening relationships with society

Integrated communication perceives communication in organizations under this convergent and unified prism, covering all aspects of communication, including sports communication (Kunsch, 2003)Ref26. Sport has unique characteristics of symbolism and an intangible character that enhances its messages when developed from effective and coherent communication practices. Hence, integrated communication is important in the sports area (Rocco Junior, 2016)Ref35. Developing an organizational identity aligned with the market positioning in sport can be the basis for a sense of belonging for individuals and supporters (Brinkmann, 2019)Ref5.

In a study that seeks to define the management process in sport, Rocha and Bastos (2011)Ref37 emphasize that entities should also be considered organizations, in this case, with the task of directing the activities of a class. This is the case of the Union of European Football Associations, UEFA, the object of study in this investigation, an institution responsible for football at the European level, affiliated with the International Football Federation, FIFA, which, in turn, directs sports such as football, futsal and beach soccer around the world. As organizations, entities must also strive for communication as an instrument for sharing meanings and strengthening the relationship with the public.

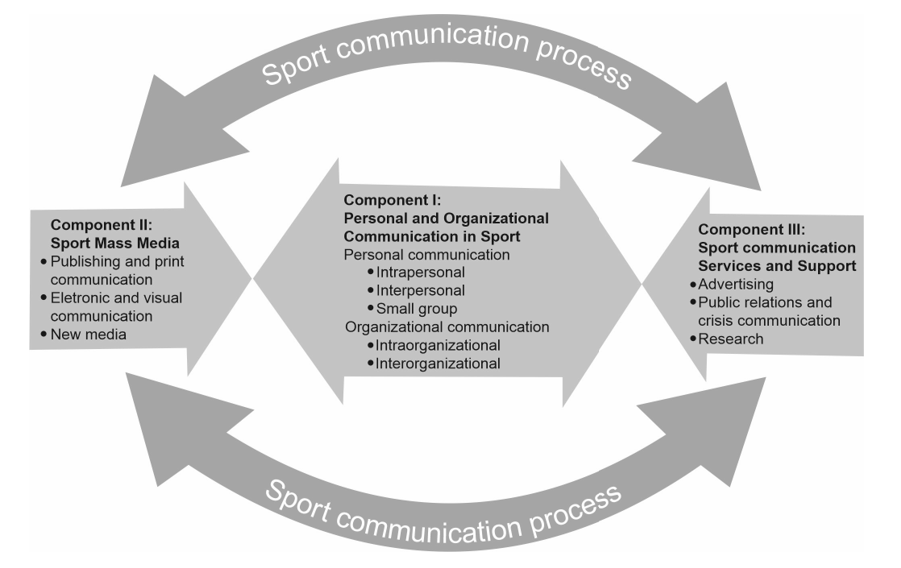

Football is a sport that motivates a participatory passion among its fans like no other popular culture can (Cegalini & Rocco Junior, 2019)Ref8. Taking advantage of this ascending line in the level of popularity, expanded by the most diverse communication channels, especially the internet, Pedersen et al., (2007)Ref33 focused on the integrated communication model developed by Kunsch (2003)Ref26, adapting it to sports communication. To this end, they divided sport-oriented communication into Personal and Organizational Communication of Sport, Sport and Mass Media and Services and Support for Sports Communication (Pedersen et al., 2007)Ref33, according to the diagram.

To mitigate the impact of sports results, sports entities are increasingly betting on communication strategies capable of creating lasting and permanent affective bonds (Ruão & Salgado, 2008)Ref40. Thus, sports organizational communication can be a tool for building identity, image and reputation. In this context, Cegalini and Rocco Junior (2019)Ref8 argue that communication with the community is essential, even if, in current times, it is a global community without borders.

European sports entities, guided by the ECA club management, began to perceive the community and social responsibility strategically, based on the communication resources that they can develop to strengthen these relationshipsRef8:

The ECA club management guide (ECA, 2015) divides the relationship with the community into three levels: short-term, with punctual and planned actions that contribute to building a solid relationship and approximation with its community of fans, locally or globally (with the help of social networks); medium-term, with the development of the construction and communication of institutional identity values; and long-term, with the elaboration of a strategic planning of social policies that bring clubs closer to their most diverse audiences (Cegalini & Rocco Junior, 2019, p. 195).

This unique opportunity for communication with the global market is increasingly present in sports (L'Etang, 2006)Ref29, which can thus catalyze messages of a social nature, create impact, and raise awareness in societies while establishing deep identity ties with their audiences.

4. Promoting social responsibility through sport

In the new organizational landscape, we emphasize that corporations have realized that they need to transcend the limited marketing relationship with their target audience (Kunsch, 2018)Ref28. As the organization is inserted in a particular environment, it will interact with it, affecting it and being affected by this environment (Duarte, 1986)Ref12. According to Kunsch (2018)Ref28, this raises awareness about the organization's responsibilities. Thus, they “position themselves institutionally, through strategically planned communicative actions” (p. 17)Ref28, namely concerning social issues.

De Woot (2017)Ref11 goes further. He believes that organizations need to play a leading role in the struggle for the progress of society. This logic converges with what one of the first authors advocated to theorize about Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) more than 50 years ago. Bowen (1953)Ref4 defines CSR as the obligation of entrepreneurs to make decisions and prescribe policies that are equally desirable for society. Therefore, it is no longer enough for organizations to develop palliative or reactive actions, placing social issues alongside their strategies and organizational mission (Tichy, McGill, & Clair, 1997)Ref45; they need to elevate social responsibility to the strategic centre of the business.

We can mention two studies that complement each other and illustrate the different approaches we have to CSR. We start with Leal et al., (2011, p. 34)Ref30 who bring a first grouping of CSR theories that focus on obtaining profit; the second approach deals with the minimum moral duties that an organization needs to observe, without losing focus on profit; the third approach related to "doing it well", where we are already moving towards a framework where it is necessary to contribute to a better world and, finally, the fourth approach, which prescribes to organizations a duty to act according to the common public interest, in detriment of shareholders.

Similarly, Garriga and Melé (2004, p. 53)Ref16 developed an overview of CSR theories that equally discuss four approaches: the instrumental theory, which perceives CSR only as an instrument of wealth creation (Windsor, 2001)Ref49; political theories, which emphasizes the social power of the corporation concerning society (Husted & Allen, 2000)Ref21; integrative theories, focused on satisfying social demands (Post & Preston, 2012)Ref34; and, finally, ethical theories, which denote the right thing to do and the need to achieve a good society (Garriga & Melé, 2004)Ref15.

Godfrey (2009)Ref17 highlighted the need for sports organizations to be imbued with the same responsibilities as other corporations concerning the relationship and commitment to the community's well-being. However, despite these different theoretical approaches, sports organizations carry out social actions mainly from two perspectives: pragmatic (doing good is good business) and noble (doing good is the right thing) (Athanasopoulou, Douvis, & Kyriakis, 2011)Ref1. According to Walters and Tacon (2011)Ref48, the sport has a favourable context for the applicability of CSR. It has a unique set of circumstances, making it possible to reach a broader, more comprehensive and plural range of people, which also implies that sports organizations use their communication tools to enhance the reach and engagement of their campaigns (Smith & Westerbeek, 2007)Ref44.

Sport can reflect social issues, such as gender differences or social inequalities (L'Etang, 2006)Ref29, as it develops in a social arena that is not limited to the universe of fans and teams (Skinner, 2010)Ref43 and can, therefore, incorporate these social concerns into their activities and strategies. The White Paper prepared by the Commission of the European Communities (2007)Ref14 endorses this premise by considering sport a growing social phenomenon that can contribute to prosperity and social developmentRef7.

“Business is being called upon to assume broader responsibilities to society than ever before and serve the wide range of human values (quality of life and quantity of products and services). Business exists to serve society; its future will depend on the quality of management in responding to changing public expectations” (Carroll, 1999, p. 282).

To frame the concepts of CSR within the scope of the sport, Pedersen et al. (2007)Ref33 refer that some authors have coined the term Sports Social Responsibility. The term provides the development of policies of social concern attributed to organizations but considering the specific prerogatives of the sports context, serving, through its natural characteristics of appeal and impact, as a bridge between the economic and social sectors (Smith & Westerbeek, 2007)Ref44. The authors explore the role that sport can play as a vehicle for implementing CSR, correlating the implicit responsibilities of sport and the corporate world. Smith and Westerbeek highlight factors inherent to the sport: communication power, appeal to young people, positive impact on health, social interaction, sustainability and environmental concerns, integration and acculturation, and direct benefits of sport (2007, p. 8)Ref44.

As the authors define it, “the corporate social responsibility of sport is pervasive and holds significant distributive power” (Smith & Westerbeek, 2007, p. 8)Ref44. It is precisely this communicative ability that sport has that guides this study. The internet has transformed the role of communication in CSR issues (Kriemadis, Terzoudis, & Kartakoullis, 2010)Ref24, imposing commitment, attendance, and responsibilities to organizations to establish this relationship with society.

5. The sustainable development goals as a beacon of social issues

In a post-cold war context of growing inequalities, especially in the underdevelopment of some countries (Hulme, 2010)Ref20, the UN identifies the need to establish a global pact to reduce poverty. The Millennium Declaration2 in 2000 was the kick-off of this joint effort by all the member states of the United Nations (Hulme, 2007)Ref19. Furthermore, it was from the need to establish goals and objectives of this document that, for 15 years, the Millennium Development Goals sought to reestablish global equity.

Eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, universalizing primary education, promoting gender equality and female empowerment, and many others (Mibielli & Barcellos, 2014)Ref32 were guidelines in this set of global objectives that aimed mainly at reducing inequalities.

Realizing the need to increase indicators beyond the 8 MDGs, the United Nations launched, in 2015, the 2030 Agenda, which foresaw the establishment of 17 Sustainable Development Goals, which then began to focus on the following aspects: Eradicating poverty; Eradicating hunger; Quality health; Quality education; Gender equality; Clean water and sanitation; Renewable and accessible energies; Decent work and economic growth; Industry, innovation and infrastructure; Reduce inequalities; Sustainable cities and communities; Sustainable production and consumption; climate action; Protect marine life; Protect terrestrial life; Peace, justice and effective institutions (Tulder & Lucht, 2019)Ref46.

Organizations are increasingly concerned about using their social networks for ESR communication (Dunn & Harness, 2018)Ref13. Tulder and Lucht (2019)Ref46 already point out that more than two-thirds of large organizations are moving towards alignment with the SDGs. The reasons, as we have already mentioned, can be noble, that is, apply sustainability-oriented strategies with a focus on a vision of forming a “better world” (Tulder & Lucht, 2019, p. 271)Ref46, or a positive reputation, where CSR communication becomes recommendable (Dunn & Harness, 2018)Ref13.

It is important to emphasize that this concern with the image of the organization before the stakeholders is addressed by Boiral (2013)Ref3 when he mentions the Theory of Legitimacy. When the organization considers actions to promote sustainable development in response to external pressures, which ends up becoming a risk since, in this logic of pressure, the organization can emphasize the communication of social responsibility to legitimize a supposed social discourse while not adopting concrete sustainability practices. Going deeper into the data from the Edelman Trust Barometer 20173, Tulder and Lucht (2019)Ref46 state that, on the other hand, the public already perceives that it is possible “for a company to take specific actions that increase profit and improve the economic and social conditions of the community where it operates” (p. 287)Ref46. The great challenge of these transformational changes that organizations must go through when observing the 2030 Agenda is transposing from rhetoric to practice (Tulder & Lucht, 2019)Ref46. For at least 15 years, organizations will need to be aware of this set of sustainable objectives that must be incorporated into their strategies, including communicational ones. Therefore, we identified in the SDGs the most appropriate reference to take as a basis for what is relevant to communicate in social responsibility. In this context, “we believe that football can be evoked as a catalyst for social visibility, insofar as it has gained importance social and cultural, great capacity to mobilize society and its institutions, which also gives it increased responsibilities” (Rocha & Morais, 2021, p. 70)Ref38.

6. Research methodology

Investigating the communication practices of football clubs aiming at social responsibility is a field still little explored, as we had the opportunity to verify in previous work (Rocha & Morais, 2021)Ref38. Like the article mentioned above, this study arises from the deepening of reflections on producing a Doctoral Thesis within the scope of the research unit LabCom – Communication and Arts. In this thesis, we analyze the communication strategies of Football clubs in Portugal and Brazil, investigating the importance they attach, as sports organizations, to the communication of social responsibility. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the communication of the Union of European Football Federations, UEFA, with a view to social responsibility. We believe that these organizations must also play an active role in this type of communication. The choice of UEFA comes naturally, as this is the body responsible for representing the national associations of Europe. On the other hand, this study is also based on the idea defended by Michele Uva, UEFA’s Director of Football Social Responsibility, that “UEFA has integrated social responsibility into every aspect of its five-year strategy for European football”. On the other hand, the Director states, “UEFA believes that football can play a lead role in promoting behavioral change on two key global issues: the environment and human rights”4. Thus, in addition to understanding the importance that the Union of European Football Federations (UEFA) attaches to the communication of social responsibility, we try to understand whether the environment and human rights are effectively among the priorities in publications made on the social network Facebook.

The choice of 365 days of observation of messages, starting with the first day of the year, is due to an option where it is possible to fully perceive seasonal campaigns, routine publications, actions around competitions and positioning in the face of possible cases of discrimination that UEFA is fighting. The year 2021 also marks the return of competitions interrupted due to the Coronavirus pandemic, such as UEFA Euro 2020, held between June and July 2021, the biggest competition of national teams organized by the entity.

Thus, in methodological terms, we chose to carry out a case study since it investigates a phenomenon in its natural environment an object of study that, analyzed in its particular context, can serve to prove, illustrate or build a theory (Coller, 2000)Ref10. From this case study, we emphasize that, although it is possible to assume how other sports organizations globally use their digital platforms for social responsibility, this trend cannot be assumed without sufficient empirical evidence to endorse our perceptions (Collazos, 2009)Ref9. He warns of the use of generalizations from specific results of case studies, which allows new lines of investigation in the future, whether to deepen the studies in the communication of UEFA’s social responsibility or to try to understand how other organizations that manage football attach importance to this type of communication. In this sense, it is essential to note that this is a particular case study, as it considers the communication carried out by UEFA on a specific platform, the digital social network Facebook, chosen considering its range and impact.

In this investigation, we also chose to use content analysis, considering that this technique would best allow us to achieve the proposed objectives, since it is “a set of communication analysis techniques that aim to obtain, through systematic and objective procedures, description of the content of the messages, indicators (quantitative or not) that allow the inference of knowledge related to the conditions of production/reception of these messages” (Bardin, 2011, p. 48)Ref2. Silva and Hernández (2020)Ref41 justify the use of content analysis as a technique that “can transform textual documents into quantitative data and formulating logical deductions through qualitative analysis, explore hypotheses, questions or assumptions and can be applied to various types of research” (p. 1). However, it is essential to emphasize that there are scientific paths that do not converge precisely on the same understanding. While Bardin (2011)Ref2 perceives content analysis as a mostly qualitative technique, Krippendorff (2004)Ref25 prescribes a view of the tool from a quantitative point of view, especially when it comes to textual analysis, a view also advocated by Kaplan, Goldsen, and Lasswell (1982)Ref23. They distinguish between content analysis and other communication research techniques, emphasizing its quantitative nature. This heterogeneity, also addressed by Carlomagno and da Rocha (2016)Ref6, does not limit the investigation; on the contrary, it enables an enrichment of the results, depending on the study's objectives, in this case, with qualitative and quantitative observations.

In a view more aligned with Bardin (2011)Ref2, Malhotra (2001, p. 155)Ref31 argues that, while quantitative research aspires to quantify data from a statistical perspective, qualitative research seeks a broader and more contextualized view to understanding the problem. In this context, our research assumes a quali-quantitative nature insofar as it seeks to stratify the data in a statistical and quantifiable dimension but also to understand the context and submit the analysis of messages to a qualified classification. Thus, we started to create a framework with different variables and criteria (Table 1), which allow us to identify the number of publications, their relation to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, the type of publications, and their impact, measured in terms of the number of likes and comments, and shares.

This is a process mentioned by Bardin (2011)Ref2, such as the systematic transformation of raw data, which must be aggregated into units for better interpretation. The challenge here is assertiveness in identifying the contents that need to be classified, striving for mutual exclusivity, as mentioned by Krippendorff (2004)Ref25, who understands that “no unit of analysis can fit into two or more categories” (p. 132)Ref25. “There must be formal, clear, objective, and written rules (completely formalized, in what is usually called a “code book” or “dictionary”) about the inclusion and exclusion of specific contents in the created categories” (Janis, 1982, p. 55)Ref22.

Although this is an exploratory work, in the next section, we present some of the main results that allow us to answer some of the questions that guided this investigation. In addition to having carried out a quantitative analysis of the number of publications according to the variables and criteria presented, we also seek to present examples of publications that fit the SGDs most identified in UEFA publications.

6. Preliminary results and first thoughts about how UEFA play the game

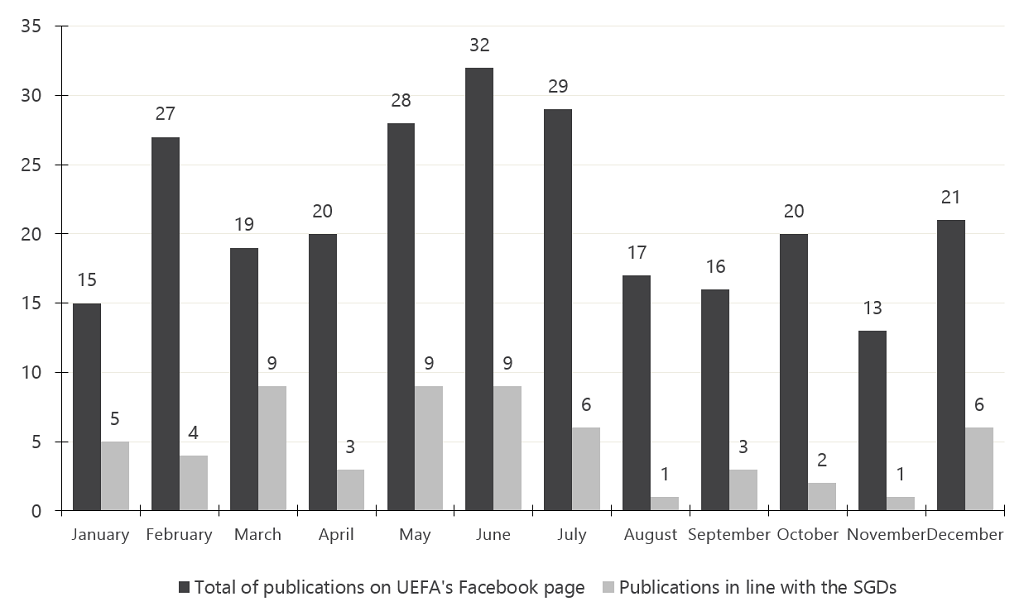

We begin the presentation of the results, highlighting the number of publications we have identified during 2021 on the UEFA Facebook page. We identified 257 publications, distributed randomly by the different months of the year, highlighting a more significant number of publications in May, June, and July (Graph 1). On these dates, particularly in June and July, UEFA Euro 2020 took place, postponed due to the pandemic, and maybe this fact can explain the number of publications.

Of the 257 publications, 77% of the messages are not aligned with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Among the messages aligned with the objectives, the largest number focus on Goal 10, oriented towards reducing inequalities, followed by Goal 5, which defends gender equality, and Goal 12, which alerts to the need for responsible consumption and production (Figure 2)7.

In a qualitative analysis dimension, to ensure the correct identification of publications associated with the SDGs, we verified the message at a textual and visual level, relating it to the indicators of global goals of each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, disregarding, at this moment, the reach of these publications. An emblematic publication related to Goal 10, which had the highest concentration of associated posts, is the one that mentions the fight against social inequality, with the #HumanRightsDay campaign5, which we highlight at the moment with a post that alerts to UEFA’s commitment to International Human Rights Day6.

The publication has a link that redirects to a document highlighting seven human rights policies championed by UEFA: Anti-racism, Protection of children and young people, Equality and inclusion, Football for all levels, Health and well-being, Support for refugees and Solidarity and rights, which converges with the global goals of the 10th SDG, where, among other indicators, it reinforces the intention to “empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, regardless of age, gender, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, economic or other”8 (Image 19).

An excellent example of a post associated with Goal 5 (Image 2), which advocates gender equality, the second with the highest incidence of publications by UEFA, with 15 posts during the year, was the #EqualGame Awards10. This campaign celebrated the work to combat discrimination and social inclusion and was incorporated into the UEFA Nations League draw ceremony, rewarding the German Football Association, Juan Mata, and Khalida Popal, for, according to UEFA, inspiring work to promote and seek equality for the women's football in the world, highlighted in this publication, with a video11. In the goals of the 5th SDG, one of the items suggests “promoting gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels”12, in line with the campaign, which also seeks to raise awareness of girls' rights and women to play football without discrimination.

The third SDG that we identified the most in UEFA publications during 2021 was the one that addresses Health and Quality. We highlight a publication (Image 313) that links to the #FeelWellPlayWell14 health and wellness campaign promoted by UEFA, which mobilizes the European coaching community to educate young people about nutrition, physical activity, mental health and substance abuse, especially tobacco and alcohol. The campaign is broadcast with a 69-second video to raise awareness of healthy practices, in line with a Health and Wellness policy developed by UEFA, in line with one of the indicators of this SDG, which aims to “strengthen the prevention and treatment of abuse substance abuse, including drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol”15.

While it is true that not all messages have to be aligned with the SDGs, we found a reduced number of publications oriented towards these goals. This lower number of posts aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals does not mean that UEFA is not working in this direction. However, on the contrary, it may be a sign that this is not yet a priority in the organization's communication or that there is still a need to promote stronger responsible social communication.

On the other hand, the data also allows us to verify that although UEFA's Director of Football Social Responsibility mentions that “football can play a lead role in promoting behavioral change about the environment and human rights”, other objectives stand out in the messages posted on Facebook.

Regarding the content of the publications, we can see that all posts have text, more than half are accompanied by photos (65%), but only 35% have video. Thus, the bet on the audiovisual dimension is made mainly based on photos. However, if we only look at the publications aligned with the SDGs, we can observe an inverse trend, as the percentage of those without photos (13,6%) is the same as those with video.

These data may indicate that a video focus is preferable when the organization wants to convey messages associated with sustainable development objectives. In this sense, it is also interesting to note that publications on objectives 3 and 10 use more pictures, while on objectives 5 and 10, more use is made of video.

Looking at the data collected (Figure 3) we can also see, concerning the impact of publications, that the 257 publications analyzed had 840,989 likes, 131,734 comments and 32,359 shares. However, in a more detailed analysis, we noticed that the posts aligned with the SDGs had only 636,61 likes, 30671 comments and 2,556 shares. These data seem to refer to relatively little impact on the part of publications that alert to sustainable development goals. On the other hand, if we look at the ten publications with the highest number of likes, we realize that only two are aligned with the SDGs. In both cases, the publications are related to goal 10, which calls for reducing inequalities.

In the case of comments, the situation is slightly different. The second publication with the most comments (13,000) is associated with Goal 10, and the third most commented is also linked to this goal. One of the most liked publications is also the one most shared, being associated, once again, with the promotion of a more egalitarian society (Image 416).

Although these are only preliminary data, they allow us to identify some trends in the goals most worked on in UEFA’s actions and publications. On the other hand, the Union of European Football Associations has sought to use its role and, in particular, the influence of football in society to promote campaigns that, in one way or another, are in line with the SDGs. We could highlight, for example, campaigns such as the “Equal Game” that seeks to combat inequalities, or the “Hope Beats Hate” campaign, that seeks to spread the message that online abuse must stop, among many others that have been promoted by UEFA, namely in the digital social networks. Finally, it is also worth mentioning that UEFA promotes several other campaigns, which were not analyzed in this article since they are explicitly shared on the “UEFA Foundation for Children” page17. In future works, in addition to deepening the analysis, with a qualitative analysis that helps identify particularly which values are promoted in these publications, it would also be interesting to extend the analysis to these other pages created by UEFA and dedicated to other subjects and specific audiences.

7. Discussion and final considerations

As an exploratory study, this work cannot answer all the questions and it should be understood as a first research effort that seeks to draw attention to the role organizations that manage football, such as UEFA and FIFA, can play if they consider all the potential around football beyond the game itself. It became evident that many publications made during the year do not address sustainable development objectives. It is also important to highlight the asymmetry in the concentration of posts on specific objectives and the absence of others. This leads us to believe that the 2030 Agenda was not observed in the strategic publications and campaign development calendar. If, on the one hand, objectives 1, 3, 5, 10 and 13, which deal with Poverty Eradication, Quality of Life and Health, Gender Equality, Reducing Inequalities and Climate Action, receive relative attention from UEFA, the same cannot be said of most of the SDGs, where we did not identify any associated publication. We also realize that the video is an important tool to communicate some values and ideas to promote an equal life. We conclude that UEFA has been playing the social responsibility game. However, we believe that it is necessary to continue to analyze the work that has been done, trying to understand what other actions are being developed and have not yet been communicated. The year 2021 was indeed marked by the pandemic, which affected the whole of society and organizations’ communication. Nevertheless, it seems to us that concerning SGDs, much can still be done in sports communication and by the leading organizations. For this reason, we want to continue to study the role that sports organizations, especially football organizations, can play in transforming society if they promote actions aligned with sustainable development goals.

In this context, it is essential to analyze what happens on social networks and outside of them, starting with the organizations themselves. It is vital to understand if there are communication plans that consider social responsibility issues or if actions and campaigns are only temporary and not actually planned. We believe that it is also fundamental to understand the practical impact these campaigns can have. To do this analysis, we need reception studies, with surveys among sports lovers, to understand their perception of the actions conducted by these organizations and the potential changes in their attitudes and behaviours.

Thus, and if those organizations play a leading role in the struggle for the progress of society (De Woot, 2017)Ref11, it is necessary to analyze whether football clubs consider the example of organizations that manage football and feel likewise impelled to develop campaigns and actions of social responsibility.

In the case of UEFA, and as we have seen in the theoretical framework, this sports organization carries out actions from a noble perspective (Athanasopoulou, Douvis, & Kyriakis, 2011)Ref1. Although not all the publications we analyzed are completely aligned with the SGDs, the intention is clear. It uses its power to raise awareness of several issues that go far beyond what is happening within the field. The question that remains to be answered is not related to the attention that UEFA has paid to social problems but to communication. In this sense, we defend the realization of works that analyze the public's perception, considering particular moments other than those that precede the games and where alerts are usually made to various social problems. Finally, it also seems essential to us that in future analyses, we try to understand what role old and current athletes, considered idols for many, may have in the communication of these organizations.

We do not doubt that “UEFA is serious about using the power of football to have a positive impact on global issues”18, but we question whether this seriousness and concern has been efficiently communicated and reached different audiences.

Referencias bibliográficas

1) Athanasopoulou, P., Douvis, J., & Kyriakis, V. (2011). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in sports: antecedents and consequences. Paper presented at the 4th Annual EuroMed Conference of the EuroMed Academy of Business.

2) Bardin, L. (2011). Análise de conteúdo (Vol. 70). São Paulo.

3) Boiral, O. (2013). Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Accountability Journal Accounting, Auditing.

4) Bowen, H.R. (1953). Social responsibilities of the Businessman. University of Iowa Press.

5) Brinkmann, R.L. (2019). Mídias Sociais no Esporte como objeto de estudo: análise dos artigos publicados no International Journal of Sport Communication (IJSC) entre 2014-18. 42º Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação – Belém. Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação.

6) Carlomagno, M.C., & da Rocha, L.C. (2016). Como criar e classificar categorias para fazer análise de conteúdo: uma questão metodológica. Revista Eletrônica de Ciência Política 7(1): 173-188.

7) Carroll, A. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business society, 38(3), 268-295. https://doi.org/10.1177/000765039903800303 | https://doi.org/10.1177/000765039903800303

8) Cegalini, V.L., & Rocco Junior, A.J. (2019). Comunicação corporativa e gerenciamento de reputação em organizações esportivas. Comunicação Sociedade, 41(2), 85-117.

9) Collazos, W.P. (2009). El estudio de caso como recurso metodológico apropiado a la investigación en ciencias sociales. Educación y desarrollo social 3(2), 180-195.

10) Coller, X. (2000). Estudio de casos (Vol. 30). Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

11) De Woot, P. (2017). Responsible Innovation. London: Routledge.

12) Duarte, G. (1986). Responsabilidade Social: a empresa hoje. Fundação Assistencial Brahma.

13) Dunn, K., & Harness, D. (2018). Communicating corporate social responsibility in a social world: The effects of company-generated and user-generated social media content on CSR attributions and scepticism. Journal of marketing management 34(17-18), 1503-1529.

14) Europeia, C. (2007). Livro branco sobre o desporto (Vol. 18). Serviço das Publicações Oficiais das Comunidades Europeias.

15) Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics, 53(1), 51-71. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000039399.90587.34 | https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000039399.90587.34

16) Giulianotti, R. (1999). Football: A sociology of the global game. Polity Press.

17) Godfrey, P.C. (2009). Corporate social responsibility in Sport: An overview and key issues. Journal of Sport Management, 23(6), 698-716. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.6.698 | https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.6.698

18) Gonçalves, G., & Elias, H. (2013). Comunicação estratégica. Um jogo de relações e aplicações. In: A. Fidalgo & J. Canavilhas (Org.) Comunicação digital. 10 anos de investigação (pp. 135-150). Coleção Comunicação.

19) Hulme, D. (2007). The making of the millennium development goals: human development meets results-based management in an imperfect world. Brooks World Poverty Institute Working Paper(16).

20) Hulme, M. (2010). Problems with making and governing global kinds of knowledge. Global Environmental Change 20(4), 558-564.

21) Husted, B.W., & Allen, D.B. (2000). Is It Ethical to Use Ethics as Strategy?. In: Sójka, J., Wempe, J. (Eds) Business Challenging Business Ethics: New Instruments for Coping with Diversity in International Business. Springer.

22) Janis, I.L. (1982). O problema da validação da análise de conteúdo. In A linguagem da política. Editora da Universidade de Brasília.

23) Kaplan, A., Goldsen, J., & Lasswell, H. (1982). A confiabilidade das categorias de análise de conteúdo. In A linguagem da política. Editora da Universidade de Brasília.

24) Kriemadis, T., Terzoudis, C., & Kartakoullis, N. (2010). Internet marketing in football clubs: A comparison between English and Greek websites. Soccer Society, 11(3), 291-307. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660971003619677 | https://doi.org/10.1080/14660971003619677

25) Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (Vol. 2). Sage.

26) Kunsch, M.M.K. (2003). Planejamento de relações públicas na comunicação integrada (4 ed.). Summus.

27) Kunsch, M.M.K. (2016). A comunicação nas organizações: dos fluxos lineares às dimensões humana e estratégica. In: M. Kunsch (Org.) Comunicação organizacional estratégica: aportes conceituais e aplicados (pp. 37-58). Summus.

28) Kunsch, M.M.K. (2018). A comunicação estratégica nas organizações contemporâneas. Media & Jornalismo, 18(33), 13-24. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_33_1 | https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_33_1

29) L’Etang, J. (2006). Public relations and sport in promotional culture. Public Relations Review, 32(4), 386-394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2006.09.006 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2006.09.006

30) Leal, A., Caetano, J., Brandão, N., Duarte, S., & Gouveia, T. (2011). Responsabilidade social em Portugal. Bnomics.

31) Malhotra, N.K. (2001). Pesquisa de Marketing: Uma Orientação Aplicada. Bookman Editora.

32) Mibielli, P., & Barcellos, F.C. (2014). The Millennium Development Goals (MDG): a critical evaluation. Sustainability in Debate, 5(3), 222–244. https://doi.org/10.18472/SustDeb.v5n3.2014.11176 | https://doi.org/10.18472/SustDeb.v5n3.2014.11176

33) Pedersen, P.M., Laucella, P., Geurin, A., & Kian, E. (2007). Strategic sport communication. Human Kinetics Publishers.

34) Post, J., & Preston, L.E. (2012). Private management and public policy: The principle of public responsibility. Stanford University Press.

35) Rocco Junior, A.J. (2016). Gestão Estratégica da Comunicação nos principais clubes de futebol do Brasil: Muito Marketing, pouca Comunicação. Revista de Gestão e Negócios do Esporte (RGNE), São Paulo, 1(1): 64-78.

36) Rocco Junior, A.J., Carlassara, E.d.OC., & Parolini, P.L.L. (2016). Comunicação comunitária e responsabilidade social em clubes de futebol do Brasil e da Europa: muito além do “sócio-torcedor”. Organicom, 13(24), 189-204.

37) Rocha, C.M.D., & Bastos, F.D.C. (2011). Gestão do esporte: definindo a área. Revista Brasileira de Educação Física e Esporte, 25, 91-103.

38) Rocha, F., & Morais, R. (2021). O papel do futebol no combate às desigualdades e na afirmação do papel da mulher: uma análise das estratégias de comunicação dos clubes de Portugal e Brasil no Dia Internacional da Mulher. Interações: Sociedade E As Novas Modernidades, (41), 68-93. https://doi.org/10.31211/interacoes.41.2021.a4 | https://doi.org/10.31211/interacoes.41.2021.a4

39) Ruão, T., Salgado, P., Freitas, R.d., & Ribeiro, P.C. (2014). Comunicação Organizacional e Relações Públicas, numa travessia conjunta. In: T. Ruão, R. de Freitas, Paula C. Ribeiro, & P. Salgado (Eds.): Comunicação Organizacional e Relações Públicas: horizontes e perspetivas. Relatório de um debate (pp. 16-39). Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade da Universidade do Minho.

40) Ruão, T., & Salgado, P.J. C.F. (2008). Comunicação, imagem e reputação em organizações desportivas: Um estudo exploratório. Comunicação e Cidadania. Actas do 5º Congresso da SOPCOM (pp. 328-340). Universidade do Minho, Braga.

41) Silva, D.C.d., & Hernández, L. G. (2020). Aplicação metodológica da análise de conteúdo em pesquisas de análise de política externa. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política, 33. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-3352.2020.33.218584 | https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-3352.2020.33.218584

42) Silva, S., Ruão, T., & Gonçalves, G. (2020). O estado de arte da comunicação organizacional: As tendências do século XXI. Observatorio, 14(4), 98-118. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS14420201652 | https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS14420201652

43) Skinner, J. (2010). Sport social responsibility. In: Hopwood, M., Kitchin, P. and Skinner, J. (Eds.). Sport Public Relations and Communication (pp. 69-86). Routledge.

44) Smith, A.C., & Westerbeek, H.M. (2007). Sport as a vehicle for deploying corporate social responsibility. Journal of corporate citizenship, 25, 43-54. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2007.sp.00007 | https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2007.sp.00007

45) Tichy, N.M., McGill, A.R., & Clair, L.S. (1997). Corporate global citizenship: Doing business in the public eye. San Francisco: Lexington Books.

46) Tulder, R.V., & Lucht, L. (2019). Reversing materiality: from a reactive matrix to a proactive SDG agenda. In Innovation for Sustainability, (pp. 271-289). Springer.

47) Vieira, R.F. (2004). Comunicação Organizacional - Gestão de Relações Públicas. Mauad Editora Ltda.

48) Walters, G., & Tacon, R. (2011). Corporate social responsibility in European football. A report funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme. Birkbeck Sport Business Centre Research Paper, 4, 1-101.

49) Windsor, D. (2001). The future of corporate social responsibility. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 9(3): 225-256. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb028934 | https://doi.org/10.1108/eb028934

Notas

1) Interview available on UEFA's website. “Football's social responsibility: UEFA raises its game”, https://bit.ly/3EsVy7O (Accessed 09 July 2022).

2) https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/united-nations-millennium-declaration (Accessed 09 July 2022).

3) https://www.edelman.com/trust (Accessed 09 July 2022).

4) Interview available on UEFA's website. “Football's social responsibility: UEFA raises its game”, https://bit.ly/3Cpk5I6 (Accessed 09 July 2022).

5) Post available at: https://www.facebook.com/uefa/posts/451397209689079 (Accessed 09 July 2022).

6) “International Human Rights Day 2021: UEFA’s commitment to act”, available at: https://bit.ly/3MjTqRK (Accessed 09 July 2022).

7) Figures available at: https://bit.ly/3RPEpIk (Accessed 09 July 2022).

8) Agenda 2030 available on the United Nations website at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (Accessed 09 July 2022).

9) Post available at: https://www.facebook.com/uefa/posts/451397209689079 (Accessed 09 July 2022).

10) Campaign available on the UEFA website at: https://bit.ly/3rJW21K (Accessed 09 July 2022).

11) Post available at: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=464965278589735 (Accessed 09 July 2022).

12) Agenda 2030 available on the United Nations website at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5 (Accessed 09 July 2022).

13) Post available at: https://www.facebook.com/uefa/videos/322186969504524/ (Accessed 09 July 2022).

14) Campaign available on the UEFA website at: https://bit.ly/3Mhur1v (Accessed 09 July 2022).

15) Agenda 2030 available on the United Nations website at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3 (Accessed 09 July 2022).

16) Post available at: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=344237747071693&set=a.277085627120239 (Accessed 09 July 2022).

17) Post available at: https://www.facebook.com/uefafoundation/ (Acessed 09 July 2022).

18) Interview available at UEFA website at: https://www.uefa.com/insideuefa/about-uefa/news/0269-1267f354a99e-4467f8bbb807-1000--environmental-sustainability-and-social-responsibility-uefa-s-f/(Acessed on 09 July 2022).

Breve curriculum de los autores

da Rocha, Fernando Jesús

Fernando Rocha holds a Master's degree in Strategic Communication, Advertising and Public Relations and is currently a PhD candidate in Communication Sciences at the University of Beira Interior (UBI), Portugal. He has a specialization in Communication and Marketing. He is an Associate Researcher at the Young Researchers Working Group (SOPCOM) and at LabCom – Communication and Arts, a research unit in Communication Sciences at the University of Beira Interior.

Morais, Ricardo

Ricardo Morais holds a PhD in Communication Sciences and a Master's in Journalism from the University of Beira Interior (UBI). He is currently an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Porto. He is a researcher at the project "MediaTrust.Lab - Laboratory of Regional Media for Civic Trust and Literacy" and a member of LabCom - Communication and Arts research unit.